IN THIS ISSUE

Need for nursing care may arise suddenly

Research, visit, consult. Repeat. And take all the time you can.

Make a decision, then make sure to stay engaged.

Care giving at home: It’s a tough option

Get these documents in order

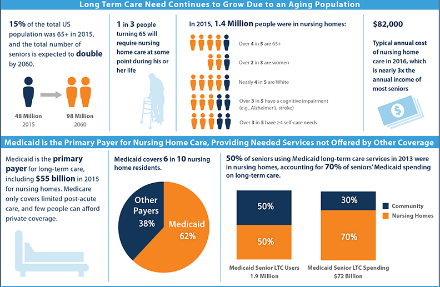

BY THE NUMBERS

1.4 million

Number of Americans in nursing homes (2015)

$100,000

Average cost per year of private room in U.S. nursing home (2017)

60%

Percentage of nursing home residents covered by Medicaid

$55 billion

Cost to Medicaid to cover qualified Americans’ nursing home care

56%

Percentage of Americans ages 57-61 who will spend at least one nightin a nursing home in their lifetime

Dear Ava Claypool,

The hurricane scenes are burned in our minds:

- Nursing home residents in Houston sitting in rising flood waters and desperately waiting for rescue,

- A Hollywood, Fla., nursing home where 12 residents died from the heat after storm damage cut off power to their building’s cooling systems,

- In Puerto Rico, a frantic nursing home operator making an unforgettable plea for help.

But good can come from bad, if it helps us stop putting off some hard research that many of us know we need to do, to help a loved one or even ourselves avoid getting put into one of these nightmare scenes of being in the wrong nursing home at the wrong time.

Let’s leap in with some helpful ideas.

Photo credit: Viral Twitter picture posted as plea for help by Kim and TIm McIntos

Need for nursing care may arise suddenly

More of us will end up in nursing homes than not. New research, from the nonpartisan RAND Corporation finds that among Americans ages 57 to 61, 56 percent will stay in a nursing home at least one night.

The average stay in a nursing home is 272 days. One in ten of us will spend 10,000 nights there.

Hospitals are under increasing pressure to move infirm patients out of their costly beds. As the nation grays and grapples with projected major increases in age-related dementia, it will be inevitable for tens of millions of American seniors. As of 2015, 1.4 million Americans, mostly seniors, were in 16,000 nursing homes.

Here’s a big challenge: Older patients and their families often struggle along, thinking they can make do until a medical crisis occurs. It might be a bout of pneumonia, a stroke, or even a urinary tract infection that pushes a senior off a cliff. A once-mobile senior suddenly may fall frequently, or become listless and bed-ridden. Or that robust colleague suddenly may not be able to stir from a chair. Moms and grandmoms, dads and grandads, suddenly can require more time, attention, and resources than most households can provide.

Hospital social workers may offer good advice (although it could be tilted toward a nearby nursing home that happens to be under the same ownership as the hospital). But the heavy lift still will be on you. That’s because a few pages of written descriptions of local nursing homes will be but the barest start. You’ve got research and thinking to do. You may wish to click here to get an excellent federal guide to choosing a nursing home.

Infographic credit: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

Research, visit, consult. Repeat. And take all the time you can.

As you consider nursing home care, you’ll need to know some key information.

How serious and chronic are your senior’s health conditions, and what kind of care and at what sustained level will they need?

Older Americans have an array of choices before them now for long-term care services. Some may try, with family and other help, to stay at home (see below on why this can be tough). Some may move into complexes that can provide increasing levels of care, from relatively independent living (apartment-like units, say, with meals provided) all the way to 24/7 nursing care. Some may thrive, mostly on their own but with the help of visiting aides or medical caregivers. Some may prefer group boarding homes, while others demand single-room privacy. Those with advanced dementia and Alzheimer’s may require not only extensive care but also secured living that prevents them from wandering into harm.

Ask your trusted friends and family what they know about nursing homes in your area. Ask your doctor and your medical specialists. Uncle Sam recently launched a site online that provides comparative information on nursing homes, including their staffing, quality of care, and record on health and fire inspections. This is boiled down into a star-rating system. It’s similar to what’s offered about hospitals. It’s still developing, but the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services deserve credit for this resource. You also may wish to look at the federal eldercare services locator site by clicking here. Or check out the online information from the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging by clicking here.

There are local government resources, too: Click here for nursing home information from the District of Columbia. Click here for Virginia, and click here for Maryland.

Nursing home care isn’t cheap. A private room can cost just under $100,000 a year, while a semi-private room goes for $85,000 annually, according to research by a major long term insurance provider. It found that the cost of nursing home care has jumped by 50 percent since 2004.

Consider affordability

Although many Americans think that Uncle Sam magically steps in to pay for all nursing home care, that just isn’t so. Medicare and Medicaid play major roles in seniors’ health care. But Medicare doesn’t cover nursing home care except for short transitions from hospital care. And to qualify for Medicaid, you must have drawn down your assets to $2,000 for an individual, $3,000 for a couple. Medicaid is the primary payer for nursing home care, spending $55 billion in 2015. If you haven’t paid much attention to the unending debate over the Affordable Care Act, you should, especially because partisans proposed to gut Medicaid. And that would leave droves of seniors at risk because they rely on the program to pay for their nursing home. Further, if partisans got their way with deep Medicaid cuts, this also would worsen the quality of care in nursing homes relying heavily on the program’s funding, creating a gaping divide for seniors between have- and have-not facilities.

Your hunt for an optimal nursing home will be driven not only by the level and cost of care but also by geography. Where do you live and how close do you want to be to your friend or loved one’s nursing home? Facilities in fancy parts of town naturally may cost more. But if you want to stay engaged with your senior—and that can be crucial to them and you—consider how far they might be in a given nursing home and how long it will take you, regularly, to visit.

Do-it-yourself Inspections

As you consider options, leave time to make multiple visits to nursing homes of interest. You do this much, if not more, when sending the kids off to college. And, unlike your youngsters, older adults may not have the resilience to bounce back if they get in the wrong quarters. So the site visits are vital. If it’s at all possible, and if you’re helping a friend or loved one find a place, go with them. Go not just during the day but also in the afternoon or night.

Common sense should be your guide, especially with your eyes, ears, and nose on high alert. How tidy, hygienic, calm, and orderly does the place seem? Is the home quiet or noisy, especially with residents in discomfort or beeping medical equipment and ringing phones? Even if a resident doesn’t have a private unit, can she find privacy? Are there places to secure her few, select valuables? Where will you chat when you visit?

Questions are great

Ask tons of questions, especially of the caregivers. (There are some excellent visitor checklists that you should read and print out by clicking here or clicking here or here.) How many nurses or aides are there – and how many do you see helping seniors? What are their credentials and training? What kind of attention are residents getting? Do staffers treat them kindly or is this just another job for them? What kind of medical services are available (pharmacy? dentistry?) What kind of activities might they participate in?

You should try to eat at the facility and insist on seeing menus for a week or so—complaints about food are huge at nursing homes. Ask what happens if a resident doesn’t like the food choices for a given meal. Do they have options? How regulated is the food service? If a resident doesn’t feel like eating at 6 straight up, can she snack and get a full meal later?

Living conditions are a critical matter. How hot or cold is the place? Is it bright and sunny or dark and dismal? Is it well maintained? How are the grounds and the surrounding neighborhood? What kinds of views are available, and can residents get outdoors? Does the home feel safe and secure?

You should ask whether the home has regular fire drills. How would residents be evacuated and cared for in an emergency? And, of course, is there a disaster plan – and how often is it tested and revised, and who oversees it to ensure it isn’t a worthless pile of papers?

Make a decision, then make sure to stay engaged

Once you’ve made a choice, you’ve got more work to do – paperwork, lots of it. You will get acquainted well with the nursing home staff as you work to get your friend, loved one, or yourself admitted. This alone may give you a great idea of your future care.

The home will help guide you. But, in general, you will need to work with doctors to provide the nursing home the full medical records for the prospective resident. This includes a disclosure of current conditions, a medical history, a list of existing medical caregivers, medications prescribed, and emergency contacts.

The facility must provide you a full detailing of costs. You will give them similar candid information on any insurance the prospective resident carries, including long-term care coverage. (LTC policies are more complex than can be discussed here – you should talk to your financial advisor about them).

The law requires nursing homes to give you detailed information on possible coverages under Medicare and Medicaid, and you get a general idea of these by clicking here.

Again, you likely will find that Uncle Sam isn’t footing the full nursing home bill for you, your loved one, or friend, so you will need to make the financial arrangements to pay for care, and you may need to set up a small account to pay for incidentals. You’ll need to ensure a durable power of attorney and an advance health directive also are in place (see below).

As with your site visits, take your time during the admissions process. Don’t let anyone rush you. You and your loved one or friend have the fundamental right while seeking medical services to informed consent, which I describe in detail on the firm website. This means that providers must give you important facts so you can make intelligent decisions about what treatment to have and where to get it. You can’t be buried in blizzard of forms, confusing jargon, or scare tales, and you can’t be pressured or hurried.

Arbitration woes

Ttoo many nursing homes will try to slip a problematic document in the pile and get you or your loved one to sign it. It will say that you waive your right to sue the home, and, instead, any disputes will be submitted to arbitration. Uncle Sam until recently had agreed with advocates for the elderly and had barred nursing homes from forcing arbitration on their patients. The Trump Administration has reversed this. That means residents and families with disputes with homes will be, as they were before, dumped into an extra-judicial system in which the decks too often are stacked against them. Their cases are heard by hired guns, many of whom benefit from extensive relationships with corporate interests who appear before them.

Forced arbitration also can be a way for nursing homes to shield from public view harms they cause to their residents. In my practice, I see the unacceptable neglect and abuse that can occur in these facilities. Some of society’s most frail and vulnerable old can be subjected to substandard or negligent care that leaves them dehydrated, malnourished, suffering pressure ulcers (bed sores) and other unexplained injuries that can lead to death. They too often are improperly restrained with physical or chemical means. Uncle Sam has tried to crack down, for example, on short-staffed nursing homes giving powerful psychiatric drugs to residents to make them easier to handle. The misuse of medications like Risperdal and Seroquel has left many older patients in zombie-like states. Journalistic investigations also have uncovered other disgusting and shockingly widespread abuse of nursing home residents, including by sexual predators and by criminal staffers, some by theft, physical harm, or through invasive photography and use of social media.

These abominations may be more quickly detected and dealt with if residents’ families and friends stay engaged with them and vigilant about their treatment. Our social contacts and relationships play a huge role in our health and well-being, including as we age. It’s wrenching enough for friends and families to make the tough decisions to get seniors into nursing home care. But their horror can be profound if, after doing so, they learn they have put loved ones or friends in harm’s way. Natural disasters can only magnify facilities’ flaws.

We all wish that victims of Mother Nature’s current calamities see a fast, full recovery. And here’s hoping that you, your loved ones, and friends stay healthy, well, happy and out of nursing homes, or that you find facilities offering wonderful care if needed.

Care giving at home: It’s a tough option

In a perfect world, the time, money, friends, family, and other resources would be abundant and available so we could age happily and well at home, and there wouldn’t be a need for nursing homes.

That world doesn’t exist.Those who struggle to care for others take on a huge responsibility. Blessed are these caregivers, most of them women. Think hard and long before joining their ranks – though economics and other causes may not leave other options.

As the New York Times recently wrote of them, based on research by the AARP and the National Alliance for Care Giving:

“The typical family caregiver is a 49-year-old woman caring for an older relative — but nearly a quarter of caregivers are now millennials and are equally likely to be male or female. About one-third of care givers have a full-time job, and 25 percent work part time. A third provide more than 21 hours of care per week. Family care givers are, of course, generally unpaid, but the economic value of their care is estimated at $470 billion a year — roughly the annual American spending on Medicaid.”

The story goes on to say:

“This volunteer army is put at great financial risk. Sixty percent of those caring for older family members report having to reduce the number of hours they work, take a leave of absence or make other career changes. Half say they’ve gotten into work late, or had to leave early. One in five report significant financial strain. Family caregivers over 50 who leave the work force lose, on average, more than $300,000 in wages and benefits over their lifetimes.”

Even worse, perhaps, is the physical and emotional toll of extended care giving. Family caregivers are more likely to experience negative health effects like anxiety, depression and chronic disease.”

Caregivers, particularly women, struggle even more because they often find themselves socially isolated and alone.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine has warned that it is “unsustainable” for America to rely on caregivers, especially as the country grays and the demand of help with the sick, aged, infirm rises. The RAND Corporation has found that challenges are increasing sharply, too, for the nation to deal with a major surge in the aged with dementia and Alzheimer’s.

Meantime, an improved economy, stiffening competition, and hikes in the minimum wage have made the cost of hiring help to care for the old and sick at home also has gotten more steep —it’s just $50,000 a year for a worker providing 44 hours a week in help.

Get these documents in order

Some important documents need to get worked up so all concerned understand an individual’s end-of-life wishes. The paperwork can be simple and easy. But it’s best accomplished after calm, thoughtful, thorough, and informed conversations. These might include friends, family, medical caregivers—especially a primary care doctor—and the affected senior.

They and the folks around them could benefit from a durable power of attorney and an advanced health care directive.

I recommend everyone fill out a health care power of attorney — aka “durable power of attorney.” It’s a simple form that accomplishes one basic important task: it appoints someone to speak for you if you cannot speak for yourself. And it takes effect only you cannot speak for yourself.

The format of the document couldn’t be simpler. In most states, you write something that says “I appoint [fill in name] to make health care decisions on my behalf when I am unable to make those decisions myself.” You sign it and have two people witness your signature, and then you give copies of the document to various important people.

As for the advance care directive, you can download state-specific forms and learn much more about these by clicking here, which will take you to the site of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. It describes the directive, briefly, in this way, saying advance care planning includes:

-

Getting information on the types of life-sustaining treatments that are available.

-

Deciding what types of treatment you would or would not want should you be diagnosed with a life-limiting illness.

-

Sharing your personal values with your loved ones.

-

Completing advance directives to put into writing what types of treatment you would or would not want – and who you chose to speak for you – should you be unable to speak for yourself.