IN THIS ISSUE

U.S. struggling with spikes in liver-harming hepatitis A, B, and C infections

Hepatitis infections exact major harms on both health and finances

Practical ways each of us can help prevent hepatitis

A few words about alcohol

Transplant policies and practices change with times

BY THE NUMBERS

2.2 million

Estimate in 2009 of number of Americans with chronic hepatitis B infection

3.5 million

Estimate in 2015 of number of Americans with chronic hepatitis C infection

1 in 12

Proportion of Americans of Asian descent, who, unknowingly, have hepatitis.

Dear Reader,

It might happen to you because you’re an adventuresome diner or traveler. Or because of where you were born, or the kind of work you do. Or because you engaged in risky sex, even long ago, or experimented with drugs, or had a blood transfusion.

Millions of unsuspecting Americans harbor virus infections in their liver. Collectively they share one name: hepatitis, but the three most common forms, which go by the letters A, B, and C, are all quite different in how you catch them and what risk they pose to long-term health.

The increasing spread of hepatitis not only imperils our individual wellness. It’s also a rising public health problem with a big hit on private and public finances.

You’ll be hearing a lot more about hepatitis in the years ahead. It could be a good time right now to learn more about what we’re up against and how we can protect ourselves and our loved ones.

U.S. struggling with spikes in infections of liver-harming hepatitis A, B, and C

Hepatitis has become an increasingly unavoidable infection, with its three common forms on the rise due to the nation’s struggles with homelessness, poverty, and drug abuse — notably the opioid crisis.

The disease’s least severe form, hepatitis A (HAV or hep A), is highly communicable and is usually transmitted person-to-person due to poor hygiene and contaminated water or food, such as tainted strawberriesor bad raw scallops. Hep A can be prevented with a vaccination, now commonly given to children.

But hep A outbreaks — once limited to a few hundred cases annually, many from fecal contamination due to food handlers not washing their hands after using the bathroom — have spiked. That’s because this form of the disease has spread wildly where the poor and homeless collect, and where intravenous drug users sell and use illicit substances, including injecting heroin and sharing and abusing fentanyl, a super potent synthetic opioid painkiller.

Federal health officials found themselves having to issue a special nationwide advisory about a hepatitis A epidemic in 2017 after outbreaks in Skid Rows in San Diego, Santa Cruz, and Los Angeles, as well as in areas around Detroit, Salt Lake City, Indianapolis, and across Kentucky. Local officials in affected areas scrambled to offer mass inoculations. But they also had to confront filthy, neglected city streets filled with desperate and homeless poor, providing them, at least in San Diego, with new public restrooms, showers, temporary housing, and other human basics to try to stem a months-long tide of new infections.

Meantime, hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) cases — spread by exposure to and exchanges of bodily fluids — also have jumped. Hep B infection always has been a worry for anyone who works in health care, where needle sticks and exposure to those with the disease can heighten caregivers’ risks. The opioid crisis here, again, shoulders much of the blame for new jumps in hepatitis B and C infections.

But the nation’s shifting demographics also play their part. The B variety, for example, is considerably more common outside the United States, and notably in parts of Asia where large segments of the population carry the infection, often from unknowing passage of the virus from mother to child during birth. One in 12 Americans of Asian descent carries the disease, and 2 out of 3 Asian Americans don’t know they’re hep B-infected, U.S. officials say. Asian Americans, by the way, make up less than 5 percent of the population but make up half of those with hep B.

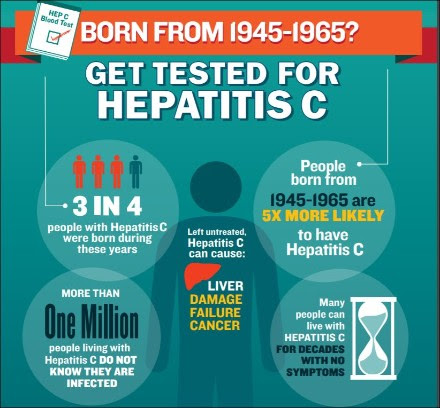

As for hep C, which is blood borne, it is an unhappy, secret surprise for baby boomers: Americans born between 1945 and 1965 are three times more likely to be C-infected than others, and 3 out of 4 of those with this infection is a boomer. Medical scientists aren’t sure why, though they suspect that boomers’ predisposition to risky behaviors may be a cause. It also is true that before the HIV-AIDS crisis of the 1990s, medical authorities didn’t know to screen the nation’s blood supplies for viruses. Some patients may have gotten hep C via transfusion, and this may have been a key pathway for the disease’s spread. (By the way, if you have tested positive for hepatitis B or C, you’re now ineligible to be a blood donor.)

If you’ve read this far and think you needn’t worry about hepatitis and its impacts, think again.

Photo credit: hepatitis virus, Assn. of Public Health Laboratories

Hepatitis infections exact major harms on both health and finances

An insidious part of hepatitis is how patients experience the disease — it can start mild. But it also can inflict a terrible and costly toll.

As the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes it: “Most adults with hepatitis A have symptoms, including fatigue, low appetite, stomach pain, nausea, and jaundice, that usually resolve within two months of infection; most children [younger] than 6 … do not have symptoms or have an unrecognized infection.”

Meantime, the CDC advises, “for some people, hepatitis B is an acute, or short-term, illness but for others, it can become a long-term, chronic infection. Risk for chronic infection is related to age at infection: Approximately 90 percent of infected infants become chronically infected, compared with 2 percent–6 percent of adults. Chronic hepatitis B can lead to serious health issues, like cirrhosis or liver cancer.”

As for those infected with hep C, it can be a “short-term illness, but for 70 percent–85 percent of people who become infected [with this type], it becomes a long-term, chronic infection. Chronic hepatitis C is a serious disease than can result in long-term health problems, even death,” the CDC says. But here’s a point worth underscoring about what the agency also says: “The majority of [C-]infected persons might not be aware of their infection because they are not clinically ill.”

That idea was emphasized by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, when the blue-ribbon group called for a campaign to reduce and even eliminate hepatitis B and C among Americans, warning that:

“In the next 10 years, about 150,000 people in the United States will die from liver cancer and end-stage liver disease associated with chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C. It is estimated that 3.5–5.3 million people— 1–2 percent of the U.S. population—are living with chronic hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C infections. Of those, 800,000 to 1.4 million have chronic HBV infections, and 2.7–3.9 million have chronic HCV infections. Chronic viral hepatitis infections are 3–5 times more frequent than HIV in the United States. Because of the asymptomatic nature of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C, most people infected with HBV and HCV are not aware that they have been infected until they have symptoms of cirrhosis or a type of liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), many years later. About 65 percent and 75 percent of the infected population are unaware that they are infected with HBV and HCV, respectively. Importantly, the prevention of chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C prevents the majority of HCC cases because HBV and HCV are the leading causes of this type of cancer.”

In other words, hepatitis exacts a costly toll now when it develops into expensive-to-treat cancers of the liver, one of the largest organs in the body and one that fulfills myriad, crucial blood filtering and biochemical processing tasks. Officials say 22,000 men and 9,000 women get liver cancer each year in the United States, and 16,000 men and 8,000 women die from the disease. The percentage of Americans who get liver cancer has been rising for several decades.

As for the money drain: In California cities alone, notably San Diego and Santa Cruz, officials spent millions of dollars battling hep A outbreaks. In San Diego, officials vaccinated tens of thousands of locals, hosed down Skid Row area streets for weeks with bleach and disinfectants, re-opened and installed dozens of bathroom facilities, and put up tent cities to better house the homeless temporarily, as the outbreak there led to just under 600 reported infections and at least 20 deaths, a surprising and disheartening toll.

The real budget-buster of hepatitis also happens to be tied up in some of the best news about the treatment of one the disease’s most difficult forms, hep C. An estimated 2.7 million Americans are C-infected, and, despite repeated pleas by public health officials for members of the public, especially boomers, to get tested, too many patients don’t get screened or get care until hep C becomes a serious illness.

In recent years, medical science has advanced sufficiently that anti-viral medications can all but eradicate hep C, with the federal Food and Drug Administration in recent times approving a single drug that, effectively, cures most patients.

But the current, mainstay drug must be taken in a closely supervised 12-week treatment. The drug’s price — which its maker defends because of its effectiveness and the major resources the medication took to develop — runs around $100,000 per patient. Many private insurers have balked at covering the full costs of this treatment, and many patients with the disease advanced enough to become a concern are older and debilitated. That means many with the infection want states, or Medicaid or Medicare to pay for this costly treatment.

The sick are battling state by state for help. California, which is the nation’s most populous state, and which has grudgingly agreed to pay for hep C drugs under its Medi-Cal program, has said it will need to set aside $1 billion just to assist patients with this infection. Besides concerns about government coverage for older, sick hep C patients, lawmakers and policy-makers also are grappling with paying for anti-viral treatment for jail and prison inmates, many who say they were infected while incarcerated.

Can a nation already staggered with health care spending of 18 percent of its Gross Domestic Product, roughly $3 trillion annually, absorb another $53 billion in estimated costs for hepatitis C care alone? Should it?

Photo credit: San Diego County. County nurse Jeanina Rumbaoa vaccinates patient outside public restroom

Practical ways each of us can help prevent hepatitis

Thorny social challenges aside, there are some concrete, simple steps we as individuals can take to prevent hepatitis infections.

For some time now, pediatricians have given children shots to prevent hepatitis A and B. The vaccinations are effective and long lasting. Parents most certainly should inoculate their children against hepatitis, and a range of other preventable illnesses. Yes, we’re taking a stand against the falsehoods and myths that mislead some well-meaning parents into avoid vaccinating their kids.

Youths and adults also may wish to get hepatitis shots. Talk to your doctor, but this may be the wise course if you’re traveling to or working in other countries or areas where infections are common, or if you may be exposed, say, through work in health care or in an adoption, to infected individuals. You may wish to be safer with this vaccination if you are a man and have sex with other men, engage in risky behaviors such as intravenous drug use, have liver disorders already or are immune-compromised. (If you have not been vaccinated and are exposed to hep A, you may benefit from a post exposure prophylaxis, aka PEP — getting the shot and a dose of immunoglobin.)

Many Americans may wish to get hep B vaccinations, too, especially if they work in health care or have partners at risk for or already hep B-infected.

Over-screening and over-testing add cost and waste to the U.S. health care system. But officials have urged Americans to talk to their doctors about getting hepatitis tests, for hep C (boomers) and for hep B (Asian Americans). Hepatitis, to be sure, is problematic for Latinos — it is a major issue for Native Americans and Alaska natives. Hep C poses notable problems for African Americans.

Besides these individual steps, you can boost the battle against hepatitis by helping to make friends and loved ones aware of this disease and its risks.You may wish to get involved in figuring out how governments may cover expensive disease care, perhaps with newer and less costly drugs coming on the market, or by persuading Big Pharma to agree to a cost-effective, large-scale license of pricey therapies. You may want to learn more about “syringe services programs,” aka “safe needle exchanges,” and how these can help reduce the intravenous spread of infectious disease. You can support policy wonks, lawmakers, and public officials as they deal with social determinants that affect not only hepatitis infections but also Americans’ overall well-being.

Let’s start simply: Praise and encourage those who practice great hygiene and safe food handling, whether at home, in the fanciest restaurants, or with food trucks and street carts. Local officials should hear from you about how much you appreciate licensing and inspection of any spot that provides good, clean food to the public. Similarly, if you’re traveling to distant spots, don’t grumble but be appreciative when authorities ensure you’re vaccinated and a good visitor or worker in areas with disease issues different, maybe more difficult than ours.

You may wish to stay informed and get involved in Washington, D.C., and environs in big, complex, and challenging efforts to deal with income inequality, poverty, homelessness, and drug abuse — and especially efforts to attack the deadly opioid abuse crisis. These matters may seem too huge and insurmountable. But they also surround us to the detriment of our daily lives, no matter how hard we may try to ignore the needy and homeless — including veterans, mentally ill men, and poor and sick women and children, as well as abused and runaway teen-agers — as they fight for life on the streets, under bridges and overpasses, and in major public buildings.

As hepatitis shows us, we can step up now to help ourselves and others together with good hearts, or we will end up paying for our neglect when our taxes must go to scour streets, pay for more and more police, and cover the higher cost of caring for our chronically sick and debilitated fellow Americans.

We can and must do better. I also always hope that you and yours stay not only hepatitis-free but also healthy and fit as a fiddle in the days and years ahead!

Infographics: federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Moderation wins again, with alcohol

While we’re talking about protecting that vital organ, the liver, let’s have a word about alcohol. Moderation is key if you want to keep your liver healthy from the effects of drinking. But too many of us aren’t imbibing in moderation — it’s just the opposite.

Booze abuse is a growing worry among women, seniors, African Americans, Latinos, and Americans of Asian descent. It plays a part in many troubles, including: fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, stroke, liver cirrhosis, several types of cancer and infections, pancreatitis, type 2 diabetes, and injuries involving vehicles and machines.

Experts warn that high-risk drinking and alcohol abuse “are disabling, and are associated with numerous psychiatric co-morbidities, and impaired productivity and interpersonal functioning.” Excess drinking, they say, places “psychological and financial burdens on society as a whole and on those who misuse alcohol, their families, friends, and coworkers, as well as through motor vehicle crashes, violence, and property crime.”

It hasn’t helped that Americans get confusing guidance on what might be acceptable levels of alcohol consumption. Recent media reports have shown that Big Alcohol — taking a page from the lobbying playbooks of Big Tobacco, Big Sugar, pro sports, and other powerful interests — has thrown around millions of its money to sway, behind the scenes, key medical-scientific research by respected institutions. A growing scandal, sadly, is enveloping the National Institutes of Health, among others.

Common sense and moderation, even in an abundance of caution, always should guidedrinkers, their friends, family, and loved ones. What may be a tiny tipple to a towering man who drinks heavily every day might well be a toxic overdose to a petite woman who rarely sips a little wine. Youngsters and seniors alike who drink so much they black out can’t really comfort themselves that their drinking is as in control as the corporate types who consumer one beer or a hard cider at lunch.

Americans have tried and failed at prohibition. But we’ve also learned the lessons of excess days of wine and roses. Whiskey and other booze can be risky for your health. You get but one life, one liver, and good health’s a gift not to be drowned and pickled in alcohol. Be smart.

Transplant policies and practices change with times

Diseases like hepatitis, cancer, alcohol abuse, and other causes of organ failure can put patients in such dire circumstance that they may need a new liver or part of one. This demand far outpaces supply, and officials who run the national system that doles out human organs are trying to make the selection process more fair.

This hasn’t been easy. The battling has gone on for years, reflecting not only the paucity of donors but also problems in regional giving and need, as well as constant concerns about inequities related to factors including potential recipients’ income, race, and previous health habits. (Liver transplants, experts note, come with heightened controversy because many recipients wore out their original livers by alcohol or substance abuse.)

In 2016, “7,841 livers from deceased donors were transplanted in the United States, while 14,000 people remained on the national waiting list,” the Washington Post reported, adding that “More than a thousand people die on the waiting list every year.”

In response to complaints, the national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network has decided after five years of heated debate, to “make more livers available in some places — including cities such as New York and Chicago — where the shortage is more severe than it is in regions such as the southeastern United States,” the newspaper said.

The New York Times reported that, under the December 2017 changes in liver transplant rules, “New York City stands to gain the most … with an annual increase of 50 livers and a 21 percent decline in deaths for those on the waiting list. Places with a higher ratio of donor livers to recipients, among them the regions that include Ann Arbor, Mich., and Philadelphia, are likely to lose.”

While controversies are likely to surround organ donation, and doctors, hospitals, and recipients will campaign for more of them, medical science also is seeking advances to improve transplant outcomes.

Recent media reports have highlighted one of these — keeping livers warm rather than cooling them after they’re removed from one patient and implanted in another. Based on practices pioneered with lungs, liver experts have testedand found the living tissue thrives more if kept warm.

Experts say warm transplantation gives them more time, lets the organ function more normally (for example, continuing to excrete bile rather than it building up), and may allow for repairative or corrective procedures to be performed on livers before they go into a new patient. The warm technique has resulted in more favorable outcomes, including in lower rates of rejection.

Photo credit: warm liver transplant process, Brian Donohue, University of Washington.

HERE’S TO A HEALTHY (REST OF) 2018!

Sincerely,

Patrick Malone

Patrick Malone & Associates